Authored by Dr. Jennifer Crane, PT, DPT, OCS, ATC of Cirque Physio.

What does current performing arts culture tell us about muscle soreness? Aches and pains? Bruises, burns, and rope rash?

“CIRCUS HURTS.”

“Train through it.”

“Tears are for home, not circus”

“Here, have some circus candy (advil/ibuprofen).”

These are all common “circus-isms” that I’ve heard, and I want to talk a bit about soreness- is it productive? How much is too much? How do you train optimally while simultaneously avoiding OVERtraining and subsequent injury?

This is a HUUUGEE topic, and I’m only going to address a small component of it in this post.

THE SORENESS RULE

BUT FIRST…

Here are the ground rules before I dive into WHAT the actual soreness rules are:

- THESE DON’T APPLY IF YOU’RE INJURED. If you have pain that is NOT from working out a muscle, GET IT CHECKED OUT by someone who’s qualified to do so.

- These rules are based on stepwise progression of overall training volume, strength or skill acquisition. This means that before you get started, you need to create multiple steps/phases of training- whether its breaking a trick down into 5 phases, or just generally increasing the number of hours you train per week. For example: if you’re an aerialist that is coming back from having a baby (and have been cleared to return to aerial by all involved healthcare providers), you should first sit down and create a multi-phase return-to-full-time-aerial plan. This must be well defined, so work with a qualified coach to do so, if you get stuck!

- Ok, sit down for this one…I’m serious, you’re not going to like it. EACH TRAINING DAY SHOULD HAVE ONE DAY OF REST BETWEEN to ensure proper recovery and adaptation to the stimulus and load!!

- Yeah, I said it. The “R” word. In this context, it doesn’t mean complete Netflix and chill bedrest status for 24 hours, it just means that if you’re working on an upper body skill, to give your upper body a break the next day. Yes, handstands count. Yes, contortion counts. Yes, vinyasa yoga counts. Yes, one day = 24 hours.

- Each step/phase in your progression should last for at least one week. This means that you should be working on whatever conditioning/training drills comprise ONE step for SEVEN DAYS- without soreness. You must be able to do step one, completely free of any muscle soreness, for 7 days before progressing to step 2. If you have soreness during step one, you stay on step 1 (with 24 hour break between each training session) until you’re doing it WITHOUT soreness. For 7 days.

- I do realize I just said the exact same thing three times. I’ve had the rest day conversation with enough circus artists to know that repetition is key, and over-defining each term is required. It is also often required for me to define how many hours are in a day, and how many days are in a week.

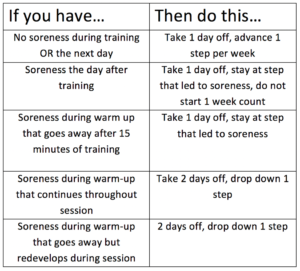

CLIFF NOTES VERSION

Overwhelmed? Here’s the cliff notes version: Pick a skill to work on, or an overall training goal. Break the goal down into at least 5 steps. Assign drills and conditioning for each step. Start with step 1, and don’t move on to step 2 until you’ve been doing it every other day for one week, without any muscle soreness.

Oh yeah…one more thing. WORK WITH A QUALIFIED COACH.

PRESENTING: THE SORENESS RULE

YOU’VE GOTTA BE KIDDING ME.

Alright, there we have it. The rules. You guys, I KNOW. Your heart rate and blood pressure just spiked, and you’re getting anxious just THINKING about all those rest days, and how slowly you think you’ll progress. I’m aware that in the circus world, these rules seem SUPER conservative.

However…as a circus PT, at least 80% of the injuries I treat are from overuse…too much training, and too little rest. These injuries tend to last upwards of 3 months (because again, no rest…) and can significantly impact performing artists career length and career quality. The kicker is, these injuries are caused predominantly by modifiable risk factors…aka, proper dosage of training and adequate rest. So yes…I understand that you’re panicking thinking about this. And yes, I understand that implementing any big change in training program is something that does NOT happen overnight, but I think these rules have a potentially huge positive impact on the overall rate of overuse injuries in circus artists, and I think there’s value to planting this seed in your minds…even if you don’t actually DO anything about it for a while!

As I said, the topic of adequate rest, proper training load and volume, as well as overall periodization of training in circus arts is a MASSIVE subject. I’ll likely have a few more posts on this topic, so if you have any specific requests, leave them in the comment section!

Development of a distance‐based interval throwing program for Little League‐aged athletes (This is the original “soreness rule” article)

Return to hitting: an interval hitting progression and overview of hitting mechanics following injury.

Upper extremity weight-training modifications for the injured athlete. A clinical perspective.

Track return to running program: UDel

DR. JENNIFER CRANE, PT, DPT, OCS, ATC

Dr. Jennifer Crane is a physical therapist, athletic trainer, board certified orthopedic specialist, and published author. She has been a sports medicine professional for eight years, and has worked with a wide variety of athletes and performing artists throughout that time. Most recently, she worked as a physiotherapist living in China with the Chinese Olympic Teams in preparation for the Rio 2016 Olympics. While in China, she worked with multiple sports teams: diving, weight-lifting, fencing, gymnastics, synchronized swimming, and track and field. Of the athletes she worked with, 18 of them went on to get an Olympic gold medal in Rio.

Now happily back in San Francisco, Jen’s practice is based at Circus Center, where she specializes in injury prevention and treatment of athletes and performing artists. When she’s not working with circus artists, she can usually be found standing on her hands, swinging on flying trapeze, or spinning on a single point trapeze.